There are also prescription drugs available that don’t have a sedative effect which can help you to sleep.

Although many prescription drugs can help you sleep, some may not help you to get the restorative sleep you need to feel your best during the day. Plus, they may be long lasting with means you can experience daytime symptoms (difficulty remembering things, dizziness, fatigue, blurred vision) after using them.

It’s important to talk to your doctor about any symptoms you may be experiencing, as well as how long you’ve been having trouble sleeping. They can then find a way to help you, so you can not only fall asleep but also feel your best during the day.

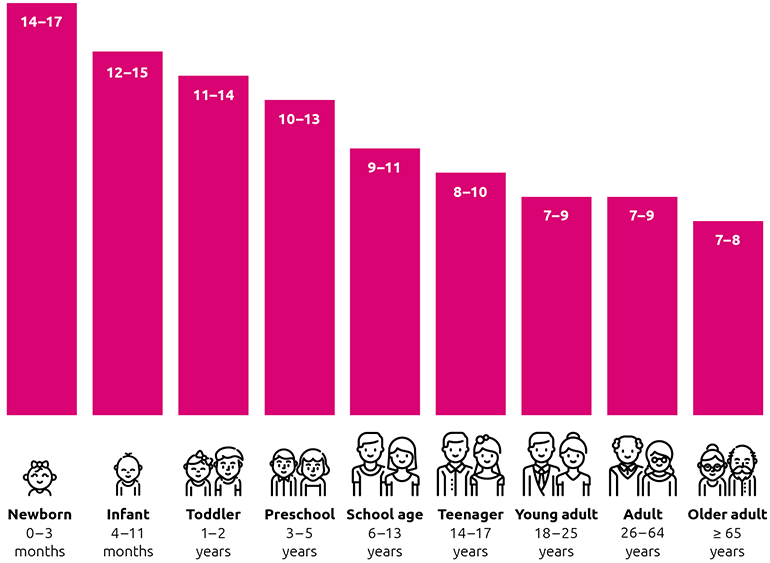

The types of prescription drugs that can be prescribed to you depend on certain factors, such as your age, as well as other medications you may be taking.

There are lots of different types. Some are recommended for short-term sleep troubles, while others are more suitable for long-term sleep problems, like chronic insomnia. The most common prescription drugs for insomnia are sedative medications, which act on your brain to make you feel drowsy and relaxed so you can fall asleep more easily. They can also help your muscles relax and may help reduce anxiety.